The Taikon Sisters

I moved to Budapest in 1973, and although I was a Roma girl, I began my studies at the Faculty of Humanities at ELTE University. At the same time, I also joined the movement for Roma rights. We collected traditional workers’ music , which we presented at workers’ hostels and Youth Clubs with our band, Monszun. For many years, people looked at me strangely: at the time, the idea of a Gypsy girl playing a public role was a real novelty. It must have happened sometime in the mid-70’s: János Maróthy, a musicologist of Budapest’s Bartók Archives, had just come home from a conference – from Sweden, perhaps. He gave me a photo as a gift and said, “there are other Gypsy women thinking like you, living on the other side of the world. Don’t feel alone.” Katarina Taikon’s picture has been hanging on my wall among my family photos ever since, encouraging me with its shy smile.

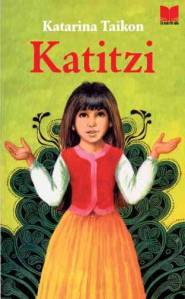

Katarina Taikon-Katitzi published a book, entitled Katitzi, in which she described the misery of her childhood in order to acquaint Swedish society with some unknown facts. In doing so, she initiated a radical process that continues to affect us today. Although Romani communities have been living in Sweden for 400 years, their lives were always characterized by the bitter freedom of travelers, the destution of tents and caravans. Only in the eyes of outsiders did their lifestyle on the fringes of society seem romantically authentic and natural.

Source: http://www.aftonbladet.se

After the publication of her first children’s book, a positive change began to take place in Swedish society, which eventually made possible the provision of proper housing for Romas and education in the Romani language. The pioneer of this movement was Katarina Taikon. Her sister, Rosa Taikon, continues even today to devote much time and energy to preserving the memory of her sister, who died at an early age; she has recommended the Katitzi volumes for translation and publication in recent /new EU member countries, and takes every opportunity to promote them on book tours.

Rosa Taikon’s video message on I’m a Roma Woman website: http://www.romawoman.org/?page=article&id=786

Yet Rosa Taikon could talk about herself as well. Not only about the fact that she was among the pillars of the movement for Roma rights, but about her life, in which she endeavored to extend her life-long profession into the realm of art. For Rosa Taikon is a world-renowned silversmith, who has applied the traditional method of the Kelderás Gypsies to jewelry making. The works of Rosa Taikon have been shown in the National Museum in Sweden.

After I succeeded in organizing the world’s first, immensely successful exhibition of Romani Fine Art in May 1979 in Budapest (“First National Exhibition of Autodidact Romani Artists), I was inspired by the warmth of its reception, and began compiling a volume entitled Romani Artists in Europe.

I sent letters to the most prominent museums and most famous cultural and social forums of Romani people, asking for their support in the form of photos and essays. It was in this way that I got to know Rosa Taikon and her amazing jewelry. When we finally met in 1985, at the Romani Art World Expo in Paris, we greeted each other like sisters. In Romani. We both felt that the long road we had travelled – from the Gypsy settlements or even from wagons, through the university to the museum (whether as an artist or manager) – had not been in vain, because we had set an example and opened possibilities for others as well.

Source: http://www.nordiskamuseet.se

The art of Rosa Taikon, which embraces varied cultures and times, from Ancient Roman bracelets to rustic Nordic designs, incorporates almost everything that can be given expression in jewelry. She works primarily with silver and semiprecious stones. A typical Romani art piece is the wedding belt with golden coins, called kushtik; in Rosa’s hands, it became an unmistakably unique metal belt. Her necklaces, rings and earrings live their own independent lives, and whoever wears them can expect to draw conspicuous attention. By choosing silver over gold as her primary material, Rosa breaks with the traditional image of jewelry as a privilege of high society, becoming an admired figure of the rebellious youth culture of the 1970’s.

Wearers of her jewelries express their open social perspective and dedication to beauty at the same time. The art of caldron welding of the Kelderás Gypsies finds echoes in her rustic designs, while the refinement and playfulness of silver create a unique tension in each of her works. To own a Rosa Taikon means possessing a piece of Swedish history.

Written by Ágnes Daróczi